After 15 years of operation, the International Civil Rights Center and Museum, which features the F.W. Woolworth’s lunch counter – the site of the country’s first sit-in – was designated a federal landmark in by the National Park Service. But the fight for that classification hasn’t come without some challenges.

In 1992, the city considered acquiring the property where the museum sits from Citizens Bank to put another parking lot in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. John Swaine, the museum’s chief executive officer, recounted the history of the center’s creation and credited Henry Isaacson, who now serves as a museum board member, for encouraging the founders to pursue the center’s creation.

“They decided to come together and raise some funds to save the property,” Swaine said.

And in 2009, the museum acquired $38 million to preserve the building.

Photo by Laila Smith.

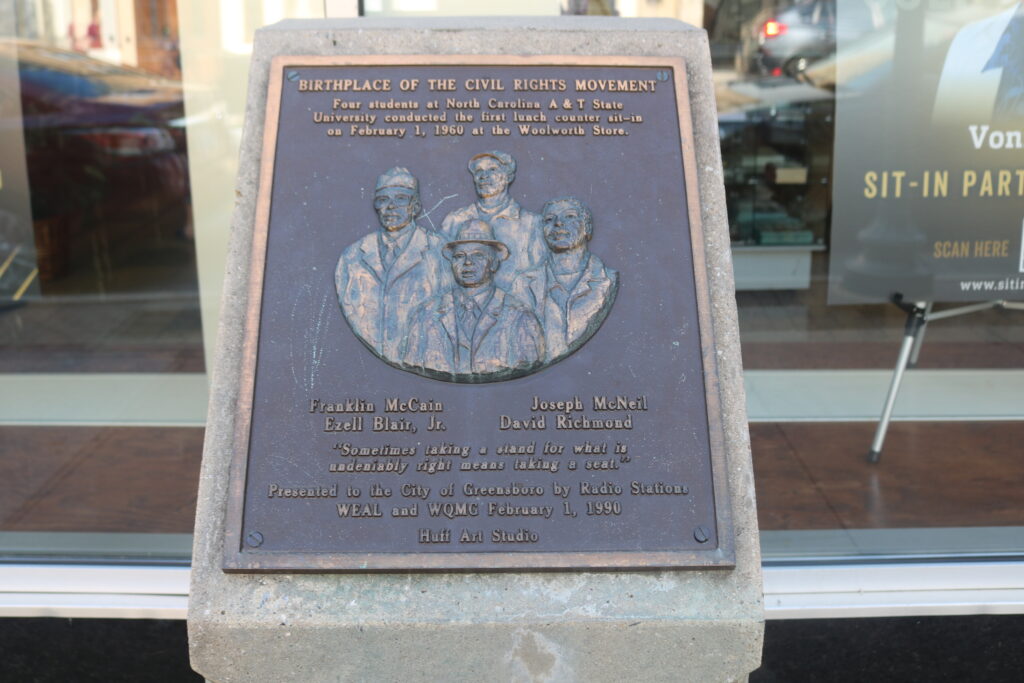

In February 1960, four young African American men staged a sit-in at the Woolworth’s, the third biggest department store in America at the time, after being denied service because of the color of their skin. Police didn’t have the authority to take action because sit-ins were one of many forms of nonviolent protest.

Efforts such as these led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 being passed, which banned segregation.

In American history, people tend to turn the pages of their books to those of famous leaders, such as Martin Luther King Jr., or significant events such as the American Revolution or slavery.

But many tend to forget about the unsung heroes of the Civil Rights Movement, a social push that ran from 1954 to 1968 and aimed to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination and disenfranchisement in the country among African Americans.

To combat this issue, African Americans began protesting, boycotting and staging sit-ins, the first of which occurred in Greensboro.

“You really need something big to happen in order to get a national historic landmark,” said Dominic Stanley, a museum tour guide and information specialist on women of the Civil Rights Movement. “If something amazing or astounding happens at your location and it has to do more with the location than the people who were in it, it still might take you two or three years to get a national historic landmark. Time was the biggest barrier for us.”

Employees at the International Civil Rights Center and Museum said they hope the federal designation will bring national attention to Greensboro while also inspiring the youth.

“We are adding to Greensboro’s history,” Stanley said.